Romano Beans with Potato, Rough Chopped Pesto and Marinated Jumbo White Asparagus

Alejandro Vergara’s Romano Bean Salad

NOTES

Romano beans are the string bean’s flat cousin and they are wonderfully seasonal. Don’t turn your nose up at canned white asparagus; the ones used here are actually a very high-end product, and can be found in Spanish specialty food shops or online (yes they are pricey at $10-$20 a can). But, be sure to get the jumbo ones, Alejandro assures me they have a far superior flavor.

RECIPE

DIFFICULTY

EASY

SERVES

6

PREP TIME

15 MINS

Salad

-

1lbRomano beans, trimmed and

-

2quartswater

-

3mediumred russet potatoes

-

2tbsolive oil

-

1canhigh quality Spanish White asparagus

-

sea salt and pepper to taste

Pesto

-

1cupGenovese basil

-

2tbschopped chives

-

1/2cuppine nuts

-

1clovegarlic, minced

-

1/2lemon

-

1/4cupolive oil

-

Parmesan cheese to taste (optional)

Sometimes I meet someone so fascinating, I am willing to overlook their wholesale disinterest in the culinary arts, and feature them on the blog anyhow. Alejandro Vergara, El Museo Nacional del Prado’s Senior Curator of Flemish and Northern European Paintings is one such character. Come to think of it, so is my dear friend and fashion stylist Kathryn Typaldos, who joined me on this lunchtime adventure in my new favorite European city, Madrid. Kathryn and I have had a running joke that she would someday contribute a recipe for diet coke and cigarettes to Salad For President, but I think her cameo in this post will suffice (thanks Kat).

No trip to Madrid would be complete without a good long visit to El Museo Nacional del Prado, an institution that holds the world’s best examples of Spanish art dating as far back to the 12th century. It is here where you will find Titian, El Greco and Velázquez hung salon style, and the mind-blowing precursor to Surrealism, The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch (check the link if you want to see naked people straddling giant strawberries, making-out in giant bubbles, hedgehogs in nuns’ habits…). The overwhelming painting galleries are bursting with hellfire and brimstone, abundant still lives and vanitas, verdant landscapes from another time, and women whose faces and hands just barely peak out from underneath mountains of taffeta and clusters of precious jewelry. There is even an entire room dedicated to portraits of 17th century “Dwarfs and Buffoons.”

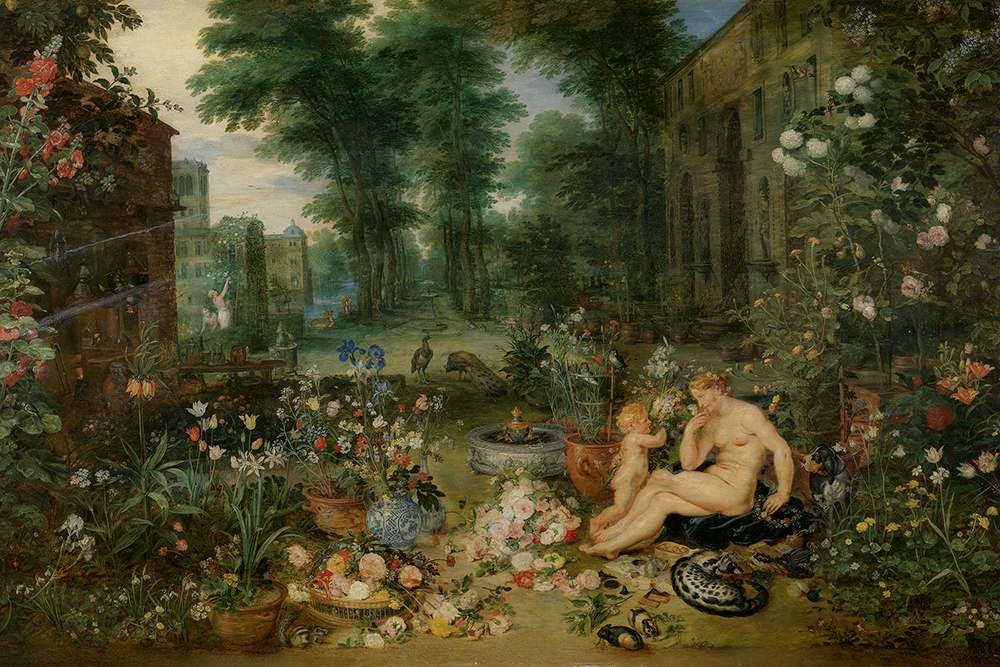

Alejandro has had the good fortune of spending the last 15 years walking these halls, telling the stories behind the master works, filling in the gaps in the history and the mysterious biographies attributed to the artists of the time. Determined to show me the paintings that focused most on food, Alejandro brought us to the famous Rubens’/Breughel collaborative works on the five senses. Each one is a complex world unto itself, Sight, Touch, Hearing and Smell, ending with an painting the deeply resonated with me after a week of eating my way through Spain – Taste. This was a gluttonous scene where the devil himself feeds an aristocratic woman from a table teeming with lobster, oysters and game hen, refilling her goblet of wine as she stuffs her face, unaware that her breast has popped out of her gown!

From the museum we headed to the store to buy some veggies, making a pit-stop at the local cafe where Alejandro gets his daily gazpacho (basically, salad in liquid form). I put him and Kat to work chopping and mincing, and we spent the rest of the afternoon shooting the shit in his home just outside the city center, where we got the inside scoop on his upcoming Clara Peeters exhibition. Peeters is the mysterious female 17th Century still-life painter from Antwerp, whose paintings are treasured but whose life story is almost entirely unknown. Peeters is credited for introducing the “Breakfast Piece” to the then emerging genre of still life painting, depicting the ingredients of a simple, everyday meal.

Alejandro Vergara in His Own Words

Julia: You grew up in Madrid surrounded by modern art, what made you specialize in Northern European 17th Century art?

Alejandro: As far as I can remember I have been sensitive to the language that paintings speak. My family exposed me to the riches of abstract painting, to modern art in general. But growing up in Madrid, I also had great respect for the artists in the Museo del Prado, for the beautiful, expressive brushstrokes of Titian and Tinroetto, Greco and Velázquez; paintings mattered to me; I saw something at stake in that world of shapes and colors, brushstrokes and stories.

JS: How were you led to Flemish art?

AV: If you decide to study paintings as your career, you need a focus. My favorite works of art have changed with time, and continue to. When I was in graduate school in New York, I was especially taken by the art of Rubens. His images are bold and powerful; they give shape to an exalted version of life. I found it fascinating that through studying his art, I was propelled into the past, and that made my world richer. I expanded from Rubens to 17th century northern art because a profession in art history demands a wider focus than on one single artist. It has been a gift to study the art of Jan Brueghel the Elder and Van Dyck, of Rembrandt and Vermeer, among many others.

JS: As an artist today, I love to collaborate with other artists. Is this a modern phenomenon, or did the 17th century artists work in this way too?

AV: Collaborations between two great masters (and not between a master and a workshop assistant) is characteristic of Antwerp painting in the 16th and 17th centuries, more than in any other place. One of the earliest known cases is a fabulous painting at the Prado, a Landscape with the Temptation of Saint Anthony, painted by Patinir (who did the landscape) and Quinten Massys (who painted the figures). When two painters like this collaborated the result was especially appreciated by discerning collectors. The same is true with the Han Bruegel the Elder / Rubens paintings of the senses in the Prado. Jan Bruegel and Rubens were friends who supported each other. Generally speaking, artists in Antwerp seem to have formed a rather collegial community. In the case of the paintings of the senses, two are signed by Jan Bruegel; the other three are not signed. This implies that Bruegel took the leading role; it was his project. He must have asked Rubens to paint the figures, knowing that this added value and status to the paintings.

JS: As an art historian who works at the Prado, what would you say are the best parts of your work?

AV: Being in contact with art, learning the ways it has been studied, interacting with people interested in art. Art has a magical power; it stirs us; it awakens a strange desire. It is fascinating to learn how paintings have been interpreted in the past: people of different times are interested in different things, and interpretations of the same work are wildly different. We can learn a lot about people by looking into how they thought about hart in the past. To me there is not better way of feeling this intimacy than by working at Prado, which house one of the world’s greatest collections of western art. It is a privilege to teach people about a work of art.

JS: In spending the day at The Prado, I felt overwhelmed by the drama of it all. You are immersed in a world of images with the most extreme subject matter – crucifixion, hellfire, women covered in hair breast feeding their babies, buffoons and dwarves, naked party goers being torn apart by wild dogs. Do you think this imagery affects your psyche on a day to day basis? Or are you somewhat immune at this point?

AV: A bit of both. I came into the love of art through abstract painting, and so I am much more sensitive to form that to content. But as an art historian, I see the drama of the history. Painting, like literature and philosophy, often considers our lives as grand, epic, dramatic projects. I also like to see life in that way; it makes it more intense.

JS: You left us to sit on a board that decides which major works of Spanish art can and cannot be sold in other countries. What is its official name, and what are some of the most incredible works that have passed through that procedure?

AV: The board is an advisory committee that works within the ministry of culture of Spain. Great and unknown paintings are sometimes brought to our attention. This is how it works: an owner asks for an export license to sell a painting at an international art market, and by law we are allowed to deny the license. The owner of course does not have to sell to the state, but often they decide to, knowing the painting cannot leave the country. Paintings are denied export licenses only in the case of exceptional works of art. The most striking recent case is a painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder of the feast of Saint Martin, and it is now in the Prado. It was a completely unknown painting by one of the great figures of the history of European art.

JS: Do you consider yourself a storyteller?

AV: Looking at paintings with you is kind of like gossiping, getting the dirt on who worked with who, who copied who etc. Yes, to some extent. I am an interpreter. But of course interpreting is not simply trying to uncover a lost truth. It is more about trying to see what about a given painting is important to me, and to my time and audience. The story telling comes into play when trying to turn my thoughts into a narrative; when trying to come up with the right words and pace; and when trying to echo the poetics of what I am seeing.

JS: Clara Peeters is an artist whose biography is almost entirely unknown. Is this a golden opportunity for you or a major pain in the ass?

AV: A great opportunity! And great fun as well. We know she was a woman who painted from approximately 1605 to 1620 – one of the few who was able to paint at the time. At least part of the time she worked in Antwerp. We know some twenty to thirty paintings by her. And that is it. I see this as an opportunity to focus on art rather than on biography. Think of how much we do know: how she painted; the type of paintings she specialized in; the type of objects she included in her paintings. Each of these issues speaks to us about a time and a place.

JS: If I were to create the Hollywood film of her life, with you as my consultant, who would we cast to play the artist herself?

AV: Don´t make that film!! … Or if you do, try to focus on the art, not the artist. Nearly all movies about artists focus on biography. The recent Turner is just another example. I am not drawn to the biographies of the painters nearly as much as I am to their art, to the language of painting. To judge from movies that I have seen, this is very hard to translate into film.

JS: It seems like what you do you do is somewhat forensic in nature. You exhume pieces of a complex and distant story and try to put together a historical narrative that makes sense to the world. Are there other activities in life that you approach in a similar fashion?

AV: I don’t think I do. Being an art historian, having written a Ph.D and many texts, devoting much of my time to studying does imply a rational approach to things. But art connects strongly with an intuitive and creative side of us, and this makes me feel that the term forensic does not really apply.

JS: Being an Art Historian is so much about pedagogy. What are you teaching now?

AV: I continue to teach occasionally at two of the leading universities in Madrid: Universidad Carlos III and I.E. University. Recently I have also put together a course that is offered through edX called “European Paintings: From Leonardo to Rembrandt to Goya” that covers European paintings from the 15th to the early 19th centuries. The course consists of 41 videos, each approximately 8 minutes long. I try single out only what is essential to each artist, to focus on the reasons why they are still relevant after many centuries.