Lacinato Kale, Quinoa, Emergo White Beans with Pecorino and Lemon Zest

David Kennedy-Cutler’s Kale Salad

POSTED UNDER

- Entree Salad,

- Fall,

- hearty

NOTES

For use in salad, I cook my quinoa in a little less liquid than normal to make sure it is extra dry and fluffy (for one cup quinoa I use 3/4 cup broth). I also cook my beans in broth instead of water to add flavor. If you can’t find Emergo Beans, substitute with Gigante beans.

RECIPE

DIFFICULTY

EASY

SERVES

4

PREP TIME

20 MINS

Salad

-

2bunchesLacinato Kale

-

4clovesgarlic, minced

-

4tbsolive oil

-

1cupquinoa, cooked

-

2cupsEmergo Heirloom Beans, cooked

-

1/2cupparsley, roughly chopped

-

1/2lemon, juiced

-

1/3cuppine nuts

-

1/2tspred pepper flakes

-

1drizzleolive oil

-

Pecorino Romano (optional)

-

sea salt and cracked black pepper

POSTED UNDER

- Entree Salad,

- Fall,

- hearty

I admired David Kennedy Cutler’s work long before I counted him among the ranks of vegetable-obsessed artists. His sculptures make the familiar strange — flannel shirts, vegetables, box cutter blades and images of his own body. Tools, edibles and clothing are flattened, scanned and printed on metal, and formed by hand into crude simulacra of the things we touch, eat and wear everyday. Yes, it’s a piece of kale in both image and scale, but through his process it is transformed into the 3D Second Life version of itself. Just when you thought you were sick of the that ubiquitous leafy green, David goes and reinvents it. Like most good art, it is tough to explain why the effect is so innately amusing.

When I spotted a folded metal piece of kale amongst the artworks at the Recess Activities fundraiser last March, I did everything in my power to win the piece and take it home. (I was so determined, my plight that evening was even recognized in an Art in America re-cap of the event). I have since purchased three of these works from David directly, which led to our date to share a real-life edible kale in one of David’s most immersive environments — his Williamsburg studio, where he improvises lunch on a daily basis.

David Kennedy Cutler in His Own Words

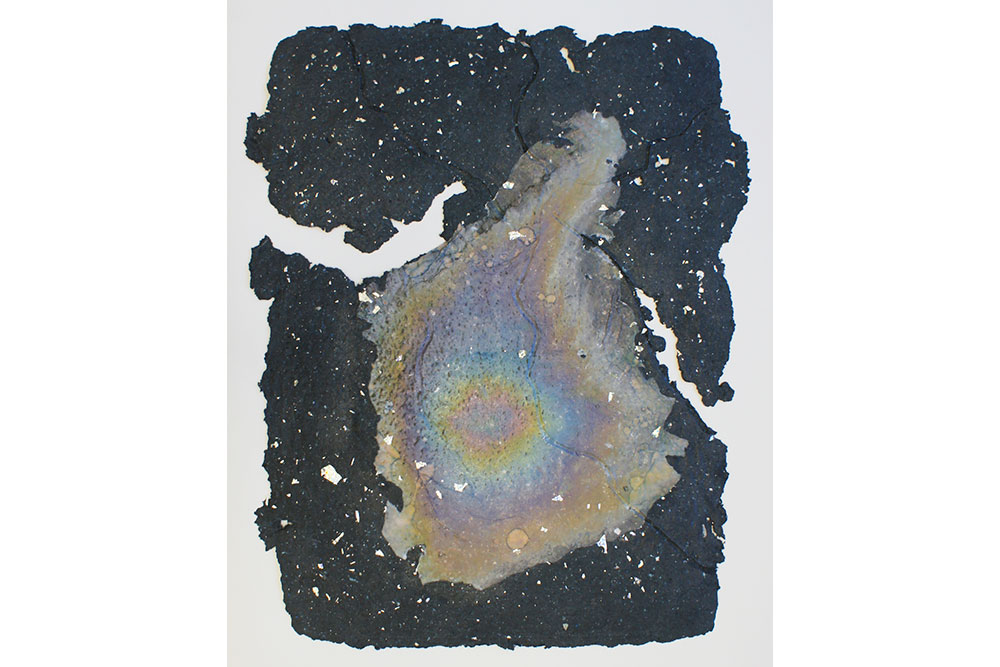

Julia Sherman: I first encountered you work at Dieu Donné, the amazing handmade paper studio and gallery. You had a show after your residency there, and you made some work that is so different than what you have in your studio now. Where did that series come from?

David Kennedy Cutler: At that point, I had been working with plastic, and thinking a lot about our notions of what is synthetic and what is natural, how oil fuels every aspect of culture, and how we engage with it everyday. The oil rainbow for me was a symbol loaded with inherent beauty and malice, and these pieces (as well as some of the sculptures I made around then) are documents of what I was calling “pscyho-geology” at the time, a riff off the Situationists use of the term “psychogeography.”

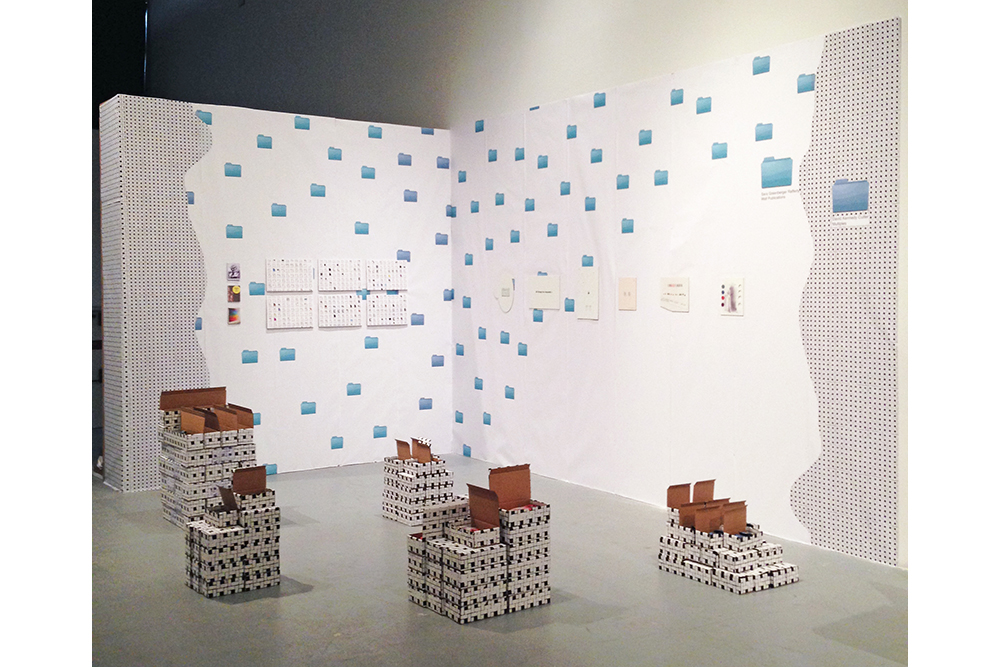

Julia Sherman: Tell me about Paper Cuts. What inspired you to create a project around editioned works?

David Kennedy-Cutler: Paper Cuts is an evolving project started by Sara Greenberger Rafferty and myself. We are both interested in creating an alternative distribution model to that of the art gallery. We’ve produced a lot of artist’s books, wall publications, prints, posters, and editioned sculptural pieces. Working this way allows us to express ideas and make work that is less exclusive, less precious, more affordable, more tactile and intimate. Unlike the work we show in a gallery context, our friends and peers can afford to own these pieces.

We also like to think about the environment where we present the work we do with Paper Cuts; in the past these have been immersive booths for the New York Art Book Fair and the LA Art Book Fair.

JS: Your wife has a very compelling job at The Met. Has her research and field of study had any influence on your practice?

DKC: My wife is a fashion historian and she works in the curatorial department at the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She has totally destabilized my notion of hierarchy within art and design. She exposes me to so many ideas I wouldn’t otherwise know about — I look at her books, go to shows with her and really benefit from her studies of textiles and the history and culture around the way we dress. It is easy to see her influence in my work; I drape my imagery like a skin or a shroud over forms and I am always playing with pattern, decoration and representation.

JS: Vegetables make a regular appearance in your work. Why?

DKC: Vegetables are in my work because they’re what I eat. I’m a vegetarian. My mom sends vegetables from a farm share in Vermont to my studio, so they naturally wander into the work. They are just some of my everyday objects that I digitally scan and make into the compositions. But I also love the taxonomy of vegetables; they have so many associative properties.

JS: What compels you to “scan everything”? Is a compulsion? A visual language? A ritual?

DKC: The vegetables, my clothes, my tools and art supplies, the floors of my apartment, my body, my wife’s body, our cats’ bodies are the materials of my daily life. By scanning and printing and layering all these things, I manipulate them until they become an image of my own compressed existence.

My impulse to scan everything is the same as the impulse to make any object. It’s a way to prove we were here, that we lived, and how we did it.

JS: Why do you think so many artists love to cook?

DKC: I grew up in Vermont, which for all of its agriculture, it actually has a very limited cuisine. My dad, who I lived with only on weekends, cooked with me and took me to ethnic restaurants in New York City. When he really loves the taste of something new or unusual, he has to pause, close his eyes and then make these almost intellectual/orgasmic sounds to honor how good the bite was. With a paradigm like that, it’s no wonder I love cooking.