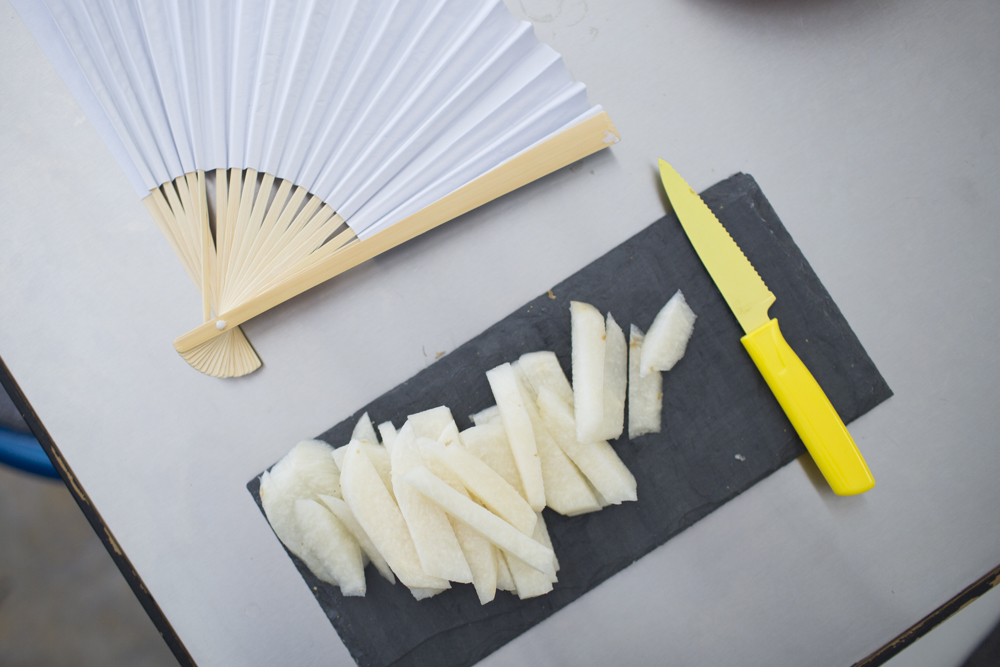

Fresh Coconut, Jicama, Lime Essential Oil and Hibiscus Salt

Saskia Wilson-Brown’s Coconut and Jicama Salad

NOTES

For this dish, Saskia used a lime essential oil perfume (edible of course), spritzing the serving bowl before adding her cut jicama and coconut. Even if you don’t have this on-hand, you can use the fragrant zest of the lime to get a similar effect. Dried hibiscus flowers are sold as a tea, most commonly found in Mexican grocery stores.

RECIPE

DIFFICULTY

EASY

SERVES

2

PREP TIME

2 MINS

Salad

-

1smallfresh coconut, cut into 1/2" slices

-

1smalljicama, cut into 1/2" slices

Hibiscus Seasoning

-

1cupdried hibiscus flower

-

2ripelimes

-

1/2tspsugar

-

1/2tspfine salt

POSTED UNDER

- los angeles

Saskia Wilson-Brown is the founder of The Institute for Art and Olfaction, a non-profit space in Los Angeles’ Chinatown neighborhood, devoted to creative experimentation with a focus on scent. Saskia wants to give artists the opportunity to use scent as a medium, one that is embedded with politics, narrative and visceral emotions.

The Institute For Art and Olfaction hosts workshops, a residency and produces large scale projects, ambitious in scale but untethered by the commercial world of perfumery. Saskia reminds me, “when you cater to nobody but a small group of like-minded nerds, well, there’s no stopping you from doing anything you want.”

Saskia Wilson-Brown in Her Own Words

JS: You yourself are an artist. Is scent your medium?

SWB: Running non-profits seems to be my medium. Or perhaps writing emails.

I was never a very good visual artist – I was always too lazy.

Julia Sherman: How did your love affair with scent begin?

Saskia Wilson-Brown: A friend gave me a book (‘The Emperor of Scent’ by Chandler Burr) and like most people who read that book, I became really interested in the field, really quickly. Originally, the plan was to make a documentary about the perfume industry, as a metaphor for the film industry – the same challenges and principles apply to both. But then I realized that there was little access to perfume-related information and materials here in the US, particularly on the West Coast. To counteract that, I started a space that allowed people to experiment with scent, in an affordable, non-commercial way. A space specifically geared towards outsiders, which is what I am.

JS: Can you tell me briefly what your vision for The Institute is? Is it a school? An art project? a Residency?

SWB: If I’m honest, it’s an art project that masquerades as a non-profit. We’re not a school: Our classes are informal, and primarily geared towards getting people informed enough to see the creative potential for perfume in the context of their other creative practices. We’re not interested in training perfumers, but we produce fun and sometimes ridiculously ambitious projects along the way. We also run the Art and Olfaction Awards for artisan, independent and experimental perfumers where we judge the year’s output, anonymously.

JS: What does the winner get?

SWB: Winners are awarded a golden pear statuette in a yearly ceremony. The awards started as a bit of an experiment, but have started to become a serious thing – thanks primarily to the hard work our judges do smelling hundreds of tiny little vials, with only a tracking number to guide them.

JS: Does the inherent subjectivity of scent pose a challenge for you and your projects?

SWB: Yes, it’s a huge challenge. One person’s relaxing aroma is another’s trauma trigger. It’s monstrously challenging to control how people react to or perceive things, and for artists that can be disconcerting. However, I think that’s the same in all mediums, to a certain degree.

In scent, we at least have the reliable capacity to trigger two things: visceral disgust, perplexed wonder. So we all have that in common.

JS: What are some of the most ambitious projects you have supported and produced through the Institute?

SWB: ‘A Trip to Japan in Sixteen Minutes, Revisited’ at Hammer Museum was a big one. We recreated a failed scent concert produced by an art writer called Sadakichi Hartmann at the turn of the 20th century. The production involved building a huge machine to propagate the scent into the room, composing a sound track and foley script, and of course composing the scents. It was a full scale collaborative effort, for every member of the team, but it was a success. We also have a large project with Pulitzer Arts Foundation in St. Louis in June, involving collecting stories from residents of the city, scenting them in a series of workshops, and putting the whole shebang into an aromatic book. It’s ambitious.

JS: What about some of the smaller projects?

SWB: Reconstructing the scent of UFO abductions based on witness accounts (a collaboration with artist Joe Merrell), for instance? Or producing a series of scented dinners with Castle Gourmet Dining; or a scented tour of famous olfactory hauntings in LA (with the Smelly Vials Perfume Club, our in-house punk rock perfume collective)…

JS: How do people respond to your space when they come in off the street?

SWB: Hmmm… It’s not a grandiose space, but it does feel creative. Typically people react to the smell (it smells good or bad, depending on what we’re working on) and the rows of noses on the back wall. And then they turn around and notice the perfume bottles. We have a lot of bottles of aromatic materials. People are pretty curious about those.

JS: Are you interested in the commercial world of perfume?

SWB: Yes and no. It feels slightly alien to our purposes at the IAO – we’re a non-profit devoted to access, and commercial perfumery is… well… not. Like all vast industries, the commercial perfume industry has its good sides (Technological innovation! New materials! Smart people!) and bad (Secrecy! Bottom lines! Capitalism!) But the commercial perfume industry, if it’s possible to lump it into one entity, feels a little bit boring to me, if I’m honest. When you’re catering to the public you’re hobbled by their demands as expressed through their purchasing decisions. But when you cater to nobody but a small group of like-minded nerds, well, there’s no stopping you from doing anything you want. In that way, the IAO is in a better position than commercial perfumery. We’re broke: But we’re free.